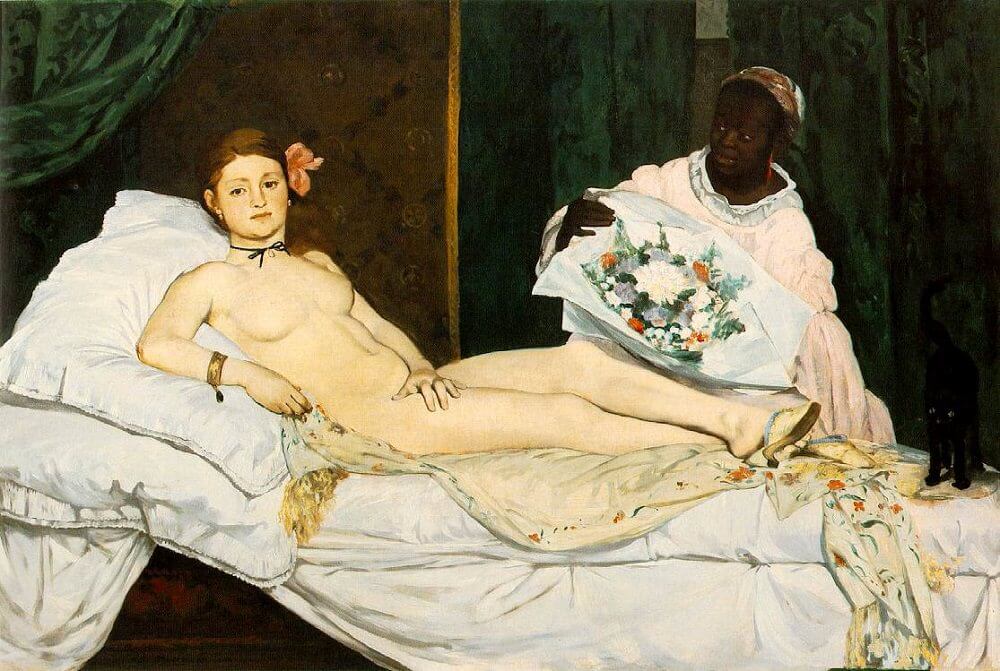

Olympia, 1856 by Édouard Manet

"Shocking" was the word used to describe Édouard Manet's masterpiece when it was first unveiled in Paris in 1865.

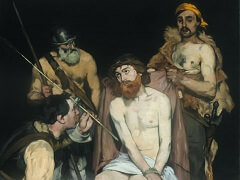

Although the nude body has been visual art's most enduring and universal subject, it has often spurred conflict. Olympia is a painting of a reclining nude woman, attended by a maid and a black cat, gazing mysteriously at the viewer. Why were visitors to the Paris gallery, already quite familiar with art featuring the naked body, so outraged by the painting that the gallery was forced to hire two policemen to protect the canvas? The objections to Olympia had more to do with the realism of the subject matter than the fact that the model was nude. While Olympia's pose had classic precedents, the subject of the painting represented a prostitute. In the painting, the maid offers the courtesan a bouquet of flowers, presumably a gift from a client, not the sort of scene previously depicted in the art of the era. Viewers weren't sure of Manet's motives. Was he trying to produce a serious work of art? Was Olympia an attempt to parody other paintings? Or, worst of all, was he mocking them?

Since composition was not his forte, Manet took it ready-made from the Venus of Urbino of Titian, hoping, no doubt, to shield himself from the critical brickbats by invoking Titian's name. As if this were not enough, he replaced the innocuous lapdog sleeping at the feet of Titian's Venus with a black cat, its back arched and tail raised. The black cat is often thought of as Satan's minion, and French chatte and English pussy designate precisely what Olympia's left-hand so emphatically refuses to the spectator's eye.

Modern scholars believe Manet's technique further inflamed the controversy surrounding Olympia. Rejecting his traditional art training, Manet chose instead to paint with bold brush strokes, implied shapes, and vigorous, simplified forms. Olympia shocked in every possible way, formally, morally, in terms of its subject matter. It had the whole range of outrage.

The Shock of the Nude presents a complex view of Manet. A member of Paris's upper-middle class, the artist was the only one of his contemporaries who didn't have to sell his paintings to earn a living. He enjoyed the benefits of his social position - living where he chose and keeping company with cultural icons of the time.

With all his privilege, Manet was still driven to prove himself to his father, who wanted his son to study law. The artist was an ambitious man, who also sought acceptance at the Salon, France's annual, government-sponsored art show, and the National Art Academy, the Academie des Beaux-Arts. In 1863 - the same year he painted Olympia - Manet submitted his painting Dejeuner sur l'herbe, or Luncheon on the Grass, to the Salon. This large, provocative painting, depicting clothed men picnicking outdoors with a naked woman, was rejected by the jury. When it was finally shown publicly that same year, it elicited a similarly negative response from the masses. Manet waited two years before submitting Olympia to the Salon.